You’d think that working at a museum might be a quiet, low-key job, but Carolyn Cross, Supervisor at the Oakville Museum, gets to delve into long buried mysteries. Occasionally she even receives a thrilling surprise — like the time Joe Johnson hand delivered precious artifacts to her.

“He said the Smithsonian offered him a substantial amount of money for [his grandfather’s] Freedom Papers,” Cross told Look Local, “but he wanted to donate them to the Oakville Museum and have them reside and be preserved where his ancestors found their freedom and laid down their roots.”

In honour of Black History Month, here’s the story of how Branson Johnson and other freedom seekers escaped slavery and made Oakville their permanent home:

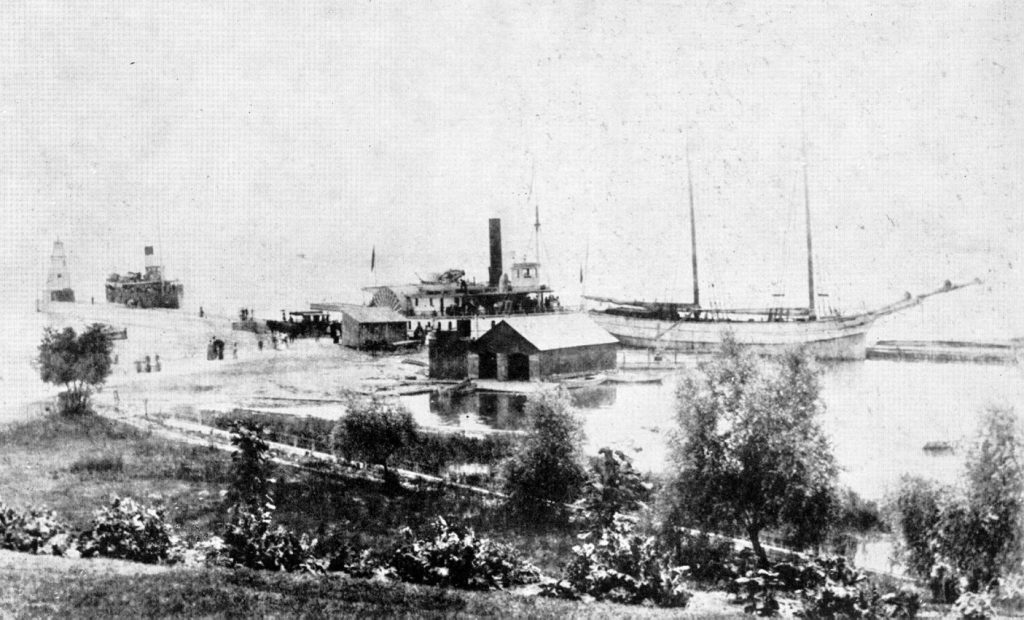

In the mid-1800s, Oakville’s harbour at the mouth of Sixteen Mile Creek was a gateway with an extraordinary role. Established in 1827 and made a legal Port of Entry in 1834, Oakville was linked to American ports that were also key stops on the Underground Railroad. This “railroad” was not made of tracks and trains, but of secret routes, safe houses and brave people, Black and White, who helped enslaved African Americans escape north to freedom.

Freedom seekers crossed Lake Ontario in the holds of grain and lumber schooners captained by abolitionists willing to risk their ships, their livelihoods and sometimes their lives. Others were hidden by Black sailors and dockworkers on Great Lakes steamers or stowed away among cargo. They arrived at a harbour that served both as a stopping place and, for some, a new beginning.

Many who reached Oakville continued on to larger Black communities in Hamilton, Toronto and southwestern Ontario. Others chose to stay and establish roots in Oakville, Bronte, Trafalgar Township and the surrounding countryside. They cleared land, built farms, opened small businesses, and founded churches that became the heart of community life.

When Oliver Parker Johnson passed a family heirloom pocket watch onto his son, Joseph, little did he know the secret it contained.

“As I scrubbed the back, the watch fell open and the (freedom) papers fell out.” – Joe Johnson, 2008.

Life here, however, was not without barriers. Black residents faced limited job opportunities, social exclusion and racism. Many worked as labourers, domestics or in physically demanding industrial jobs. Yet they also sent their children to local public schools that – unusually for the time – were not formally segregated. They served in the militia, joined town bands and sports teams, and helped shape the Oakville we know today. Their experiences remind us that Oakville was both a place of refuge and a place where the struggle for equality continued long after the journey north was over.

Meet Branson Johnson

One powerful thread in this story belongs to the Johnson family. Branson Johnson was an African American from Maryland who obtained his Certificate of Freedom in 1855, a crucial legal document in a time when Black people in the United States were required to carry “freedom papers” to avoid being seized as runaway slaves. Branson carried that precious parchment hidden inside a pocket watch as he travelled to Canada. In the 1860s he settled in Oakville, where he and his wife, Amanda Shipley, raised a large family and became pillars of local Black life.

The certificate and the very watch that protected it for so many years are preserved at the Oakville Museum. They are more than historical curiosities; they are tangible proof of a family’s determination to safeguard its freedom, and a rare window into the lived realities behind the broader story of the Underground Railroad. Generations of Black Oakvillians followed in these footsteps, working, worshipping, raising families, building businesses and contributing to public life. Their achievements helped shape Oakville’s economy, culture and character and continue to influence the town we know today.

Whether during Black History Month or any time of the year, taking the time to engage with this history is a meaningful way to honour those who sought freedom here, and to ensure their courage, resilience and achievements remain part of Oakville’s shared story for generations to come.

Carolyn Cross is Supervisor at the Oakville Museum

By Carolyn Cross