Kitty-corner to the bustling hub of McMaster University and Children’s Hospital, you’ll find 600 acres of preserved paradise. Birdwatchers flock to the boardwalk that meanders through the marshland, but back in the early 19th Century, hunters frequented the spot for its hearty waterfowl population. Captain Thomas Coote, a British naval officer, was one of those hunters. He spent many days pursuing the land for fowl in the 1780s. Rich in history and named in Captain Coote’s honour, “Cootes Paradise” is a crucial wildlife habitat and the only remaining wetland in western Lake Ontario. But there were other uses for this popular spot. Because of its sheltered location, accessibility, and tendency to freeze at a suitable depth, it was an ideal spot to harvest ice. Before the development of refrigeration, ice harvesting was an important activity for many communities across Ontario. It provided a much-needed income source and helped sustain local economies. The practice continued until well into the 20th century when artificial cold storage methods became more widespread.

Natural ice was used domestically to preserve food, and was also an essential element of commerce throughout the 19th and early 20th Centuries, with many industries relying on it for refrigeration. Breweries utilized extensive quantities to cool their wort before the advent of artificial means. Railway shipping used such a considerable volume that the Canadian National Railway maintained its own ice operation on Lake Simcoe, with steamboats packed full of natural ice to keep goods fresh while enroute.

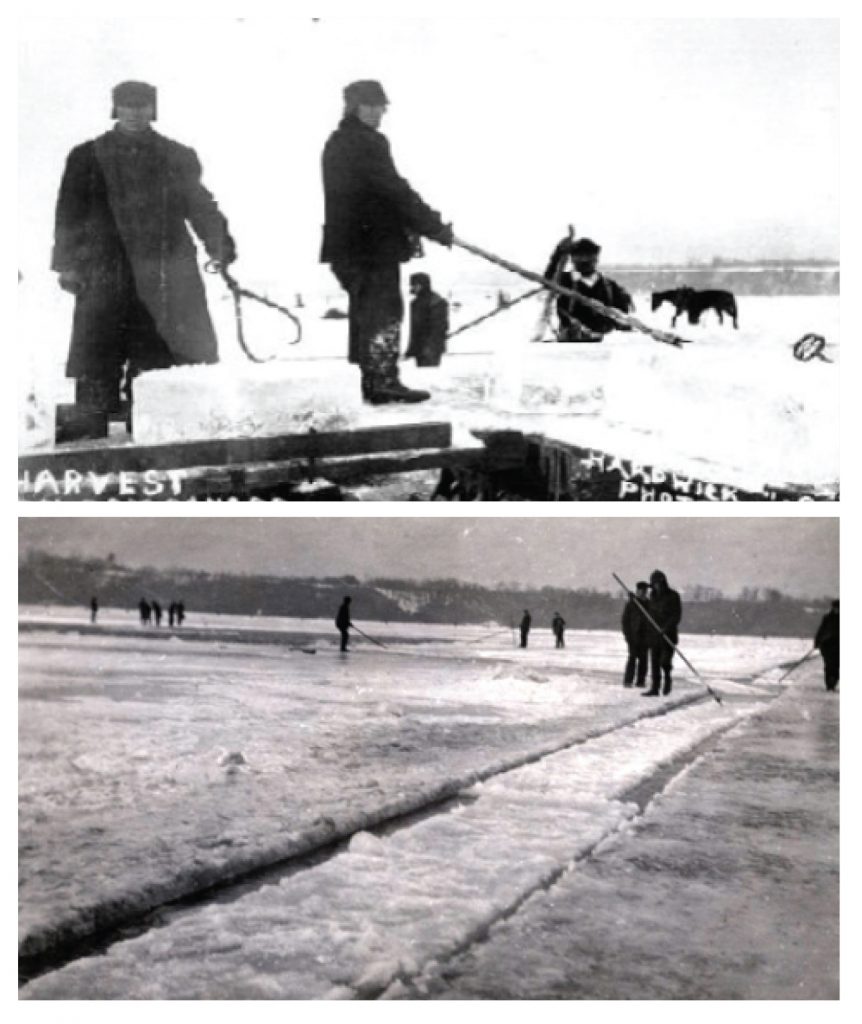

The harvesting process involved cutting large chunks of ice, called “cakes,” up to twenty inches thick, with longhandled saws and loading them onto sleds pulled by horses or oxen. The harvested blocks were then transported off the lake, packed in straw and sawdust, and stored in icehouses until sold off in the summer months. The practice was an arduous job that required a great deal of skill, effort, and perseverance. Drowning and hypothermia were a dangerous and very real possibility, as workers and animals risked falling through the ice.

For many years, ice harvesting from Cootes Paradise and the adjoining Burlington Bay, known now as Hamilton Harbour, was a significant source of employment for the local community and provided ice to many cities around Lake Ontario. At its peak in the early twentieth century, over 600 workers were employed in the trade, cutting ice daily while the conditions were favourable. Over 60,000 tons of ice were cut in a typical winter season.

Many ice harvesters were farmers, and there are strong parallels in the language and equipment used in the process. Ice blocks were referred to as “the winter crop” and cut with a specialized “ice plough”using the same draft animals used to work the land. An example of overlap between farming and ice harvesting was the Raspberry family, whose 1864 farmhouse still stands on the north side of the marsh. The Raspberrys had a dairy farm and operated an ice-cutting business in the winter. In her journal, then-teenage Elva Raspberry tells us how in the winter of 1912, one of her brothers bought his own ice cutter to help with the family business.

Today, Cootes Paradise is a protected area – and while ice harvesting in the marsh is a thing of the past, this picturesque and naturalized gem is a popular spot for leisure activities like canoeing, kayaking, and fishing. Cootes Paradise is owned and managed by the Royal Botanical Gardens (RBG), which plays an integral role in conserving and protecting these precious wetlands for generations to come. The Raspberry Farm is now the RGB Arboretum.

Ice harvesting is still occasionally practiced in Canada, serving as an important touchpoint with history and our continued dependence on the natural world. As we work towards a more sustainable future, it helps to remember our roots and the traditions that sustained us in the past.

by Julian Kingston